The reason British Prime Minister chose early elections

Max Lin

2017-04-28 09:42:21

With one bound? Theresa May is making a dash for freedom. The prime minister’s calculation is that a decisive general election victory on June 8 would bestow a personal mandate, the right to set her own agenda, and, this above all, the authority over her own party she needs to negotiate Brexit. A glance at the opinion polls tells you the stars will never be more favourably aligned.

Received wisdom had it that Mrs May was perfectly comfortable governing in the shadow of her predecessor David Cameron. Had she not said many times that the present parliament would run its full course until 2020? Received wisdom has taken quite a battering lately. If there was a justified element of surprise in her announcement it was because this cautious, deliberative politician has a deserved reputation for risk aversion.

Doing nothing was the bigger risk. Mrs May was a Remainer, albeit a reluctant one, during last year’s referendum campaign. She will never be trusted by the anti-European ultras on the Conservative right for whom a hard Brexit is the soft option. With a small parliamentary majority, it was already evident they could take her prisoner during negotiations with the other 27 member states of the EU. She needed to shift the dynamic. The alternative was to hold on to office without power.

The election gives her permission to escape the straitjacket of Mr Cameron’s 2015 manifesto and, always assuming she wins, choose her own cabinet. Mrs May has made no secret of what she thinks of her predecessor. The kerfuffle and subsequent U-turn over proposed tax changes in the March budget were an unwelcome reminder of his legacy. As for the cabinet, word in Whitehall has it that Boris Johnson, the foreign secretary, is among those whose future claim to a cabinet seat depends on just how energetically he campaigns for Mrs May.

Snap elections can go wrong, of course, as Edward Heath discovered in February 1974. In the midst of a battle with the trade unions, the then Tory prime minister went to the country with a question that he always intended to be rhetorical: “Who governs Britain?” The voters replied by choosing Harold Wilson’s Labour opposition.

Voters will not thank Mrs May for dragging them to the polls again. Nor will they be impressed by the flimsy pretence that she was forced into the decision by the Brexit manoeuvring of the opposition parties. The politics here is all about the Conservative party. By reneging on a solemn pledge, the prime minister does nothing to raise popular trust in the political class.

This is not, though, 1974. Wilson was a political master. He had served six years as prime minister. Jeremy Corbyn is no Wilson. The far left Labour leader is more comfortable in the company of Latin American revolutionaries than voters in Doncaster or Dorset. Prospective prime ministers need one thing above all else: credibility. Picture Mr Corbyn framed in the doorway of 10 Downing Street. Labour MPs now charging towards the Tory guns do so in the expectation many will be cut down on June 8.

The election will not disrupt the Brexit negotiations, not least because serious bargaining cannot begin until after Germany goes to the polls in the autumn. Nor should the prospect of a hefty Conservative majority revive hopes among pro-Europeans of a soft Brexit. The decisions to leave the single market and the customs union were taken by the prime minister, and Mrs May is not about to abandon her distinctly illiberal view of immigration. That said, a convincing victory would shift some of the parameters.

Just as importantly, it would change the texture of the negotiations.

Eight months into the job, Mrs May has begun to face up to the complexity of the challenge. She cannot, as she thought until quite recently, expect a bespoke deal with the EU that would offer the best of all worlds.

Britain will have to make compromises and concessions. Hence Downing Street’s new willingness to countenance a transition period and signals that Britain will accept large numbers of European migrants for many years after Brexit. More such concessions will have to be made, not least in recognising that if it wants to retain a close relationship with some EU agencies Britain will have to afford the European Court of Justice a role in disputes resolution.

A substantial win for the Conservatives in June will not end the divisions among Brexiters — not least between those who see the departure from Europe as an opportunity to strike a more nationalist, protectionist pose and free trade globalists who dream of creating what Whitehall officials have cruelly dubbed “Empire 2.0”. A strong personal mandate, though, would give Mrs May a margin of manoeuvre.

All this, of course, tells only half the story. There remains the small matter of what the other 27 EU member states are prepared to offer. The Brits are prone to forget that other European states have politics too. So the financial markets should not become over-excited. What can be said is that if the odds last week on a deal being struck during the Brexit talks were no better than 50:50, they have shortened somewhat in favour of an agreement.

A step forward, then, rather than a great bound.

Related news:

- Polyurethane best anti fatigue floor mats antifatigue kitchen mats, anti slip stair mats anti slip mats for stairs, anti slip mat for kitchen

- Polyurethane no slip bath mat non skid mat floor foam mats cushioned kitchen mats cushion mat

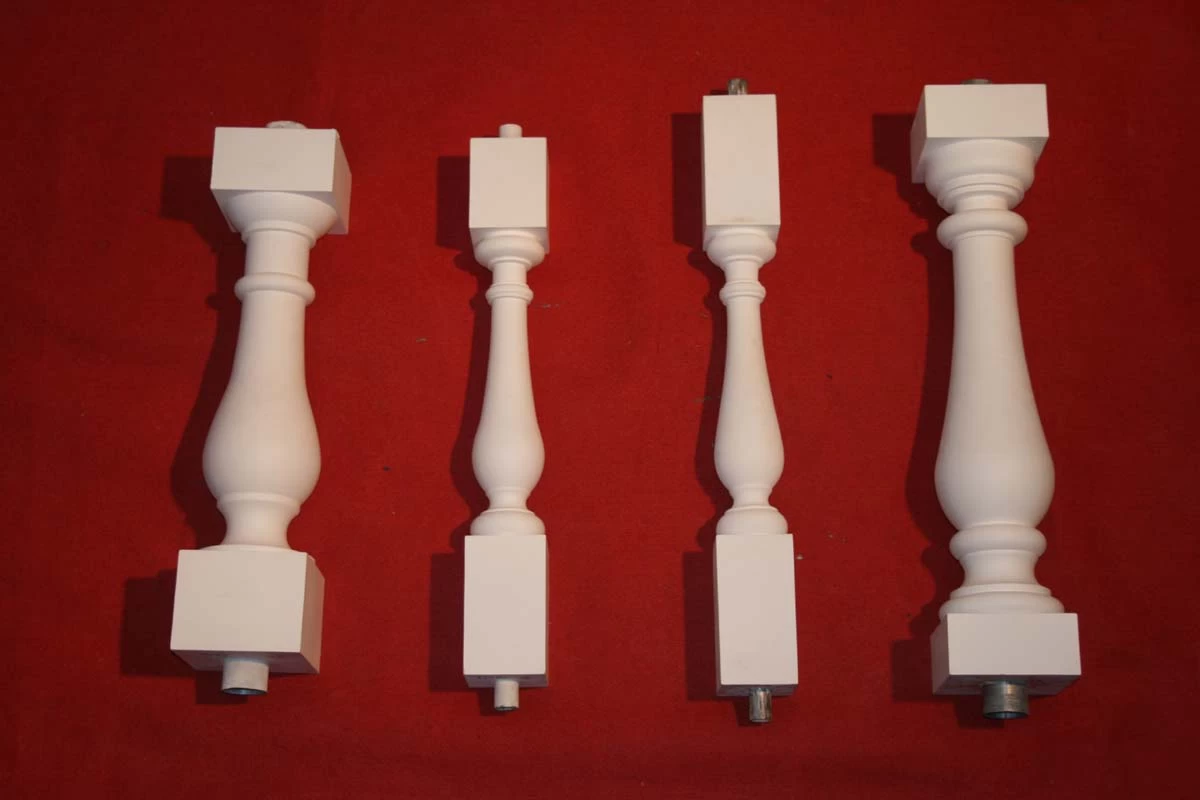

- wrought iron balcony balustrade.exterior balustrades.terrace balustrade.iron balustrade

- balustrades for sale.balustrade outdoor.stainless steel balustrade.decorative balustrade

- baluster mold,stair baluster,railing baluster,balcony baluster