Management makeovers bring in peer reviews for pay

Max lin

2016-08-18 15:35:35

Dana Minbaeva does not know how her career appraisal will turn out this year — or whether it will even take place. Her organisation has freed team leaders to experiment before deciding whether to change its performance management.

Appropriately enough, Prof Minbaeva studies appraisals and staff feedback for Copenhagen Business School.

Hers is not the only employer tinkering with staff ratings and reviews. In the past three years, General Electric, Microsoft, Deloitte, Accenture and Cisco Systems are among many that have announced reform of, or actually reformed, their performance systems.

Ratings are in the line of fire. Staff have long complained that they lead to a “rank and yank” process, where people rated lowest on a bell curve get forced out. In turn, that can drive team members into vicious competition with their colleagues. “People responsible for [software] features will openly sabotage other people’s efforts,” one Microsoft engineer told Vanity Fair in 2012. Microsoft ditched forced ranking a year later.

When not toxic, ranking systems can be baffling. One team leader at a UK consultancy says he is asked to rate staff on three dimensions, “two of which I’ve frankly never understood, however many times I’ve discussed it with human resources”.

If such crude rankings are dying, though, employers are still unclear what will replace them. They fret about how to gather enough information to decide on pay and promotion.

The future of performance management as a whole is only slightly easier to predict, but the annual career appraisal is fast disappearing. Where it survives, it is transforming into a process of constant feedback. The inspiration, in many cases, is bottom-up “Agile” product development, in which progress towards goals is regularly reassessed.

Ashley Goodall, who started to introduce a new system at Deloitte before moving to Cisco to lead a similar project, says companies are no longer asking: “Do you have five ratings or seven ratings on a scale, or annual reviews? They’re looking at the whole edifice.” For a while Cisco ran with no traditional process: “You can just stop doing it and it turns out that the sky doesn’t fall.”

One reason for change is that form-filling and bell-curve analysing are hugely inefficient. Mike Preston, Deloitte’s chief talent officer, says: “We were spending so many hours proposing a rating, debating a rating, communicating a rating, that we really didn’t spend time developing people.”

Accenture’s chief executive set off a wave of approval last year when he said the consultancy would “get rid of 90 per cent of what we did in the past”. Its staff were spending 21 hours each, 8m hours in total every year, on performance management. Sixteen of those hours were devoted just to process.

Companies are not, however, trying to recover all the wasted hours. They want to redeploy them. Janice Semper, a performance management expert at GE, says the industrial group’s managers now devote more time to “coaching and pushing decision-making down in the organisation” — a big change from Jack Welch, then chief executive, urging them to draw a “vitality curve” and force out the worst-performing 10 per cent in any team.

Reformers believe younger workers are happier measuring and updating performance and targets regularly using mobile apps than they are waiting 12 months. “Imagine if Fitbit [the wearable fitness tracker] only sent you an email at the end of the year,” argues Kris Duggan, founder of BetterWorks, which sells goal-setting software.

In the programmes being rolled out at Deloitte and Cisco, based on an ap-proach developed by consultancy Marcus Buckingham, managers use a combination of regular “check-ins”, backed up by instant staff engagement surveys and quarterly performance snapshots. GE calls its regular discussions “touchpoints”; its informal feedback sessions are known as “insights”.

Transparency is another element common to the latest appraisal methods. Accenture, which hopes to have implemented a change for all 373,000 employees by midyear, asks teams to share strengths, agree priorities and adjust them based on open assessments of how the work is going.

Companies are also trying to devolve responsibility for feedback and performance reviews to smaller units, in the belief peers are better at identifying laggards quickly and dealing with them.

Accenture has a pilot scheme to delegate pay decisions to individual teams, some with as few as 30 members. “This was the area I was a little nervous about, because we don’t want rewards to bec-ome a free-for-all,” admits Ellyn Shook, the group’s chief leadership and human resources officer.

Critics question whether the reforms are even focusing on the right problem, since the fact that humans love feedback and hate ratings is not exactly new. W Edwards Deming, the US management expert who revolutionised Japan-ese manufacturing quality, wrote in the 1980s that rating “nourishes short-term performance, annihilates long-term planning, builds fear, demolishes teamwork, nourishes rivalry and politics”.

His followers believe companies should fix faulty ways of working, not obsess about individual performance, which is bound to vary. Formal ratings should be dropped, Kelly Allan, a consultant and adviser to The Deming Institute, says: “Once you hear you’re a three out of five you can’t hear anything else.”

GE is collecting views from 30,000 staff who have been trying out a world without ratings. Ms Semper says there is “a lot of momentum” behind its new performance “conversations” and an understanding that ratings may detract from that process. Under GE’s approach, she believes team leaders will have more data with which to reward people appropriately. The same philosophy informs the Cisco and Deloitte programmes, which generate a scatter chart of team performance, rather than a single number, allowing managers to spot outliers and assess how individuals are doing more fairly and accurately.

Old habits may be hard to kick, though. Accenture’s feedback shows team leaders still want a framework, which Ms Shook calls “guardrails”, to help them assign pay.

Some team leaders, brought up on the old system, may resist the change. An HR executive at one big European company says managers set in the old ways simply use new continuous-feedback tools to record the traditional annual appraisal. Steve Hunt of SAP SuccessFactors, which supplies such tools, says one company had trouble restructuring staff after it ditched its rating system. “They ended up asking ‘Can we use compensation increases as a proxy [for individual performance]?’” he says. “That’s crazy.”

Prof Minbaeva says that as long as performance management schemes fit corporate strategy and everyone agrees with them, their precise structure may not matter. She points out that Danish managers already use MUS, an acronym for the Danish term meaning “employee development conversation”. When they saw the multinationals’ reform plans, “they shrugged their shoulders and said: what’s new?”. As for her business school’s experiments with performance management, “I wouldn’t be surprised if they come back with a system that’s only slightly different”.

Appropriately enough, Prof Minbaeva studies appraisals and staff feedback for Copenhagen Business School.

Hers is not the only employer tinkering with staff ratings and reviews. In the past three years, General Electric, Microsoft, Deloitte, Accenture and Cisco Systems are among many that have announced reform of, or actually reformed, their performance systems.

Ratings are in the line of fire. Staff have long complained that they lead to a “rank and yank” process, where people rated lowest on a bell curve get forced out. In turn, that can drive team members into vicious competition with their colleagues. “People responsible for [software] features will openly sabotage other people’s efforts,” one Microsoft engineer told Vanity Fair in 2012. Microsoft ditched forced ranking a year later.

When not toxic, ranking systems can be baffling. One team leader at a UK consultancy says he is asked to rate staff on three dimensions, “two of which I’ve frankly never understood, however many times I’ve discussed it with human resources”.

If such crude rankings are dying, though, employers are still unclear what will replace them. They fret about how to gather enough information to decide on pay and promotion.

The future of performance management as a whole is only slightly easier to predict, but the annual career appraisal is fast disappearing. Where it survives, it is transforming into a process of constant feedback. The inspiration, in many cases, is bottom-up “Agile” product development, in which progress towards goals is regularly reassessed.

Ashley Goodall, who started to introduce a new system at Deloitte before moving to Cisco to lead a similar project, says companies are no longer asking: “Do you have five ratings or seven ratings on a scale, or annual reviews? They’re looking at the whole edifice.” For a while Cisco ran with no traditional process: “You can just stop doing it and it turns out that the sky doesn’t fall.”

One reason for change is that form-filling and bell-curve analysing are hugely inefficient. Mike Preston, Deloitte’s chief talent officer, says: “We were spending so many hours proposing a rating, debating a rating, communicating a rating, that we really didn’t spend time developing people.”

Accenture’s chief executive set off a wave of approval last year when he said the consultancy would “get rid of 90 per cent of what we did in the past”. Its staff were spending 21 hours each, 8m hours in total every year, on performance management. Sixteen of those hours were devoted just to process.

Companies are not, however, trying to recover all the wasted hours. They want to redeploy them. Janice Semper, a performance management expert at GE, says the industrial group’s managers now devote more time to “coaching and pushing decision-making down in the organisation” — a big change from Jack Welch, then chief executive, urging them to draw a “vitality curve” and force out the worst-performing 10 per cent in any team.

Reformers believe younger workers are happier measuring and updating performance and targets regularly using mobile apps than they are waiting 12 months. “Imagine if Fitbit [the wearable fitness tracker] only sent you an email at the end of the year,” argues Kris Duggan, founder of BetterWorks, which sells goal-setting software.

In the programmes being rolled out at Deloitte and Cisco, based on an ap-proach developed by consultancy Marcus Buckingham, managers use a combination of regular “check-ins”, backed up by instant staff engagement surveys and quarterly performance snapshots. GE calls its regular discussions “touchpoints”; its informal feedback sessions are known as “insights”.

Transparency is another element common to the latest appraisal methods. Accenture, which hopes to have implemented a change for all 373,000 employees by midyear, asks teams to share strengths, agree priorities and adjust them based on open assessments of how the work is going.

Companies are also trying to devolve responsibility for feedback and performance reviews to smaller units, in the belief peers are better at identifying laggards quickly and dealing with them.

Accenture has a pilot scheme to delegate pay decisions to individual teams, some with as few as 30 members. “This was the area I was a little nervous about, because we don’t want rewards to bec-ome a free-for-all,” admits Ellyn Shook, the group’s chief leadership and human resources officer.

Critics question whether the reforms are even focusing on the right problem, since the fact that humans love feedback and hate ratings is not exactly new. W Edwards Deming, the US management expert who revolutionised Japan-ese manufacturing quality, wrote in the 1980s that rating “nourishes short-term performance, annihilates long-term planning, builds fear, demolishes teamwork, nourishes rivalry and politics”.

His followers believe companies should fix faulty ways of working, not obsess about individual performance, which is bound to vary. Formal ratings should be dropped, Kelly Allan, a consultant and adviser to The Deming Institute, says: “Once you hear you’re a three out of five you can’t hear anything else.”

GE is collecting views from 30,000 staff who have been trying out a world without ratings. Ms Semper says there is “a lot of momentum” behind its new performance “conversations” and an understanding that ratings may detract from that process. Under GE’s approach, she believes team leaders will have more data with which to reward people appropriately. The same philosophy informs the Cisco and Deloitte programmes, which generate a scatter chart of team performance, rather than a single number, allowing managers to spot outliers and assess how individuals are doing more fairly and accurately.

Old habits may be hard to kick, though. Accenture’s feedback shows team leaders still want a framework, which Ms Shook calls “guardrails”, to help them assign pay.

Some team leaders, brought up on the old system, may resist the change. An HR executive at one big European company says managers set in the old ways simply use new continuous-feedback tools to record the traditional annual appraisal. Steve Hunt of SAP SuccessFactors, which supplies such tools, says one company had trouble restructuring staff after it ditched its rating system. “They ended up asking ‘Can we use compensation increases as a proxy [for individual performance]?’” he says. “That’s crazy.”

Prof Minbaeva says that as long as performance management schemes fit corporate strategy and everyone agrees with them, their precise structure may not matter. She points out that Danish managers already use MUS, an acronym for the Danish term meaning “employee development conversation”. When they saw the multinationals’ reform plans, “they shrugged their shoulders and said: what’s new?”. As for her business school’s experiments with performance management, “I wouldn’t be surprised if they come back with a system that’s only slightly different”.

Related news:

- Polyurethane best anti fatigue floor mats antifatigue kitchen mats, anti slip stair mats anti slip mats for stairs, anti slip mat for kitchen

- Polyurethane no slip bath mat non skid mat floor foam mats cushioned kitchen mats cushion mat

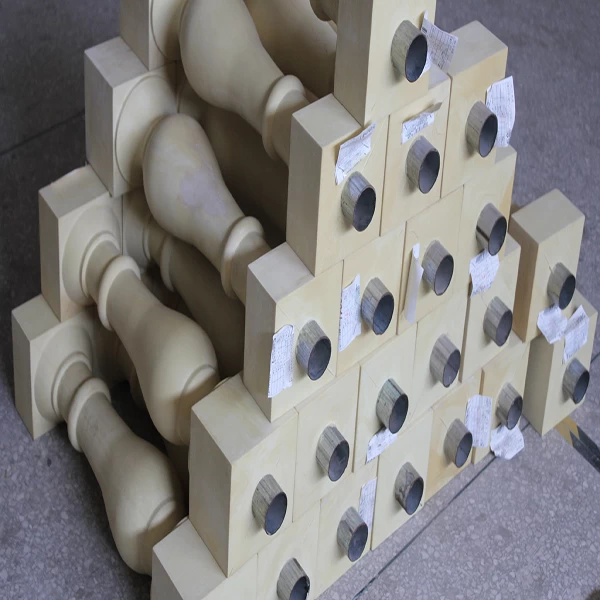

- wrought iron balcony balustrade.exterior balustrades.terrace balustrade.iron balustrade

- balustrades for sale.balustrade outdoor.stainless steel balustrade.decorative balustrade

- baluster mold,stair baluster,railing baluster,balcony baluster