Let employees dare to say no

Max lin

2017-05-15 16:03:01

“I don’t ask questions. I simply comply with the instructions given to me.” So said Malusi Gigaba, South Africa’s new finance minister, after Jacob Zuma, the country’s president, appointed him to the job last month after firing Pravin Gordhan.

Far from obeying Mr Zuma’s instructions, Mr Gordhan had asked questions, persistently, about corruption and what he saw as inappropriate government spending. Rating agencies greeted the dismissal of Mr Gordhan and the appointment of Mr Gigaba by cutting South Africa’s credit rating to junk. Tens of thousands of South Africans took to the streets in protest at Mr Zuma.

The protesters, and the rating agencies, understood that a country whose senior officials ask no questions when confronted with dubious behaviour is heading for ruin. The same is true of companies. Arthur Andersen, Enron and Lehman Brothers all crashed because people inside them, seeing their organisations taking wrong turns, did not ask their superiors: “Why are we doing this?”

By contrast, when Jes Staley, Barclays’ chief executive, ordered staff to find out who had sent two uncomplimentary letters about a newly hired employee, they did not run off to do his bidding. They pushed back. Barclays’ compliance department had classified the letters as whistleblowing and told Mr Staley that any attempt to track down the writer was not allowed.

When Mr Staley tried a second time to find the letter writer, enlisting a US law enforcement agency, someone inside the company reported him to the board. Mr Staley is now under investigation by regulators in the UK and US. Barclays’ board has formally reprimanded him and plans a substantial cut to his bonus.

Whatever the outcome of this murky saga — it is not yet clear whether this was a true case of whistleblowing or anonymous malice — the Barclays system seems to have worked. An attempt by the boss to brush aside the rules failed.

After a series of scandals, most damagingly over Libor manipulation, there are Barclays staff prepared to say: “However senior you are, what you are asking me to do is wrong and I am not going to do it.” Righteous disobedience of this sort is seldom career-enhancing, but it can help ensure the company’s health and even survival.

Most employees seldom confront such stark “really, must I?” orders from their bosses. But many face everyday managerial boneheadedness — instructions that, in their needless rigidity, damage the company, its customers and its reputation.

Last week’s order to United Continental cabin crew to remove four passengers from an aircraft about to take off from Chicago was an excellent example. Having failed to find volunteers to leave the plane to make way for United employees travelling to take charge of another flight, the airline nominated four passengers to leave and, in videos seen around the world, called in airport security staff who dragged out and injured the most recalcitrant, a Vietnamese-American doctor.

It is harder to persuade passengers off a flight after they have boarded it than when they check in, or at the gate. But airlines have more at their disposal than the $800 United was offering passengers to leave the plane. They could have told passengers their next flight would be business class, or that they could have a free flight in addition to the next day’s one. If there were still no takers, they could have offered free return flights to Paris or Bangkok (safe in the knowledge that the volunteers would be able to take advantage of the offer only in off-peak travel periods when there were empty seats anyway).

There are enough passengers, even those already on the plane — or “boarded and luggaged and situated”, as Oscar Munoz, United’s chief executive, put it — who are ready give up their seats if the price is right.

Mr Munoz, who issued a series of badly received statements, now says he understands that his flight attendants need more freedom to act sensibly. “We do empower our frontline folks to a degree, but we need to expand and adjust those policies to allow a little bit more common sense,” he said.

It will take a determined effort, and a long time, to implant that culture in the company. Employees need more than empowerment. They need to feel they have the right to say no, as Mr Gordhan and some at Barclays did. Blind obedience may please the boss. But those who demand it do not deserve to be in charge.

Related news:

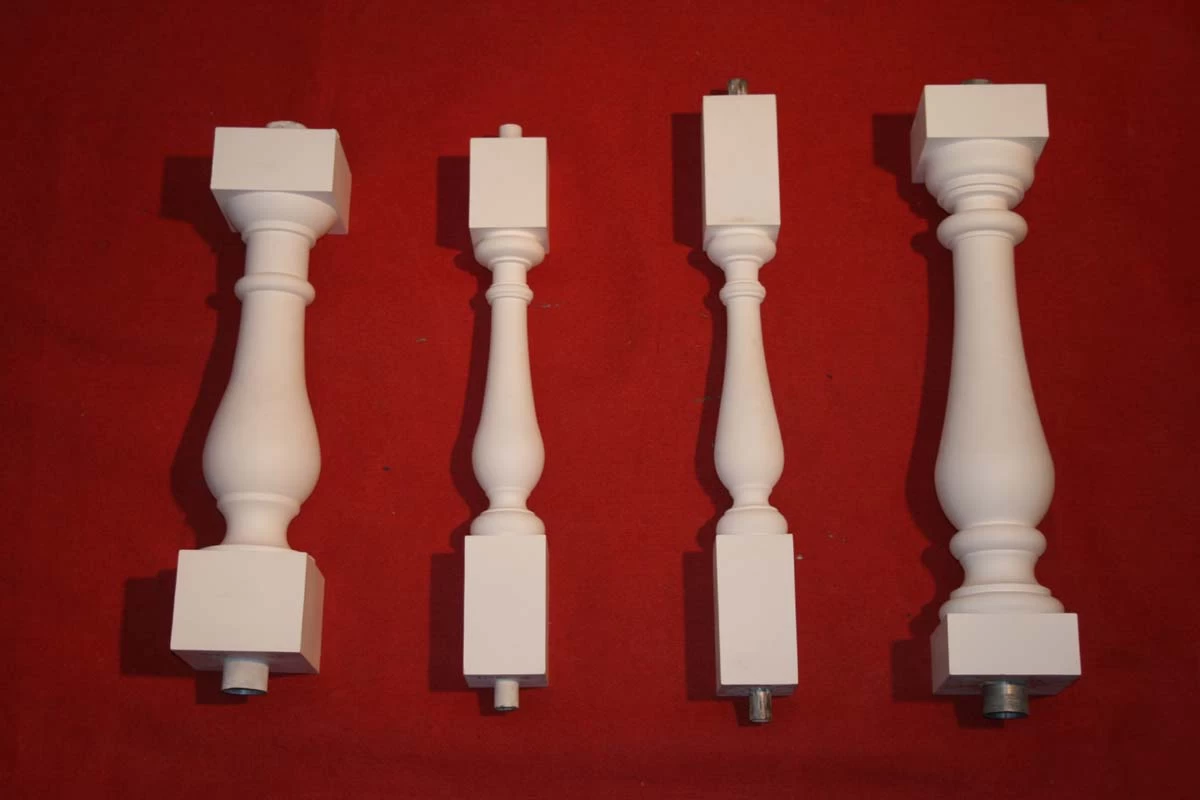

- PU rigid foam baluster, traditional design rigid foam balusters, customizable PU balusters design, outdoor balusters for balcony

- Polyurethane no slip bath mat non skid mat floor foam mats cushioned kitchen mats cushion mat

- wrought iron balcony balustrade.exterior balustrades.terrace balustrade.iron balustrade

- balustrades for sale.balustrade outdoor.stainless steel balustrade.decorative balustrade

- baluster mold,stair baluster,railing baluster,balcony baluster